A Measure of Masculinity, by Charlene Dykstra

Blog Entry One // Blog Entry Two // Blog Entry Three

To view a working bibliography for this project, click here.

Blog Entry One, March 4th 2016

Researching the Standards of Masculinity in the Early 1900s

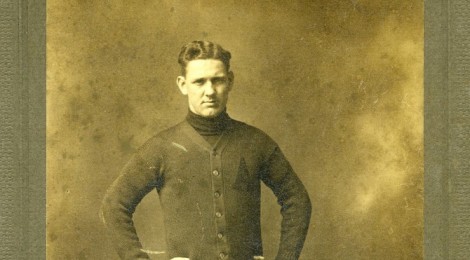

“A picture is worth a thousand words” has always been a popular phrase and it holds especially true when a picture is over a hundred years old. While researching artifacts from the 1903-1904 Purdue University school year, I came across a photograph of an unidentified football player from the Carlton A. Wilmore Papers in folder 2 of 4 in Box # 1 and decided to nominate it for our semester project because it is an intriguing example of how memories were preserved in the early 1900s. Wilmore attended Purdue University as a student of the class of 1906 until soon after the Train Wreck of 1903, when he was severely injured. He then decided to move to Alabama to attend what is now Auburn University, but the archives here do contain a small collection of artifacts from his years as a Boilermaker. The photograph comes from this small collection which contains Wilmore’s personal possessions from the early 1900s, and along with other objects that I found in the collection, it embodies the social norms of masculinity for a male student during the years 1903-1904.

Description

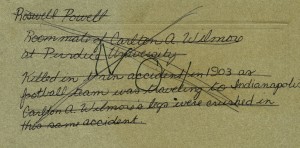

The object is a mounted photograph of a football player posing for an individual sport photograph. The man is dressed in the football uniform that was common during the early 1900s and is posed and looking at the camera in a stern and serious manner. It is impossible to tell from the photo how tall the man is, but he appears strong, wide-shouldered and confident in the way he commands the viewer’s attention. The portrait appears heavily staged, drawing out the most prominent features of the man in the directed pose which suggests that he was going for the manliest look he could achieve for this photo. The photograph is black and white, and although it is slightly discolored from the passing years in storage, it is fully intact otherwise. However interesting the photograph itself is, I find that the back of the mounted cardboard is the most intriguing part of the piece. What I assume to be Carlton A. Wilmore’s original writing identifies the man in the picture as his roommate in 1903, Roswell Powell, and also details how Powell died in the Train Wreck of 1903, during which Wilmore also was injured.

Note on back of unidentified Purdue football player photograph. From MSA 293, the Carlton A. Wilmore papers.

However, someone has crossed out and written over the original paragraph with the bold letters, “ NO!” in a different pen ink which implies that the information underneath it is incorrect. As I looked through similar photos in the Wilmore folder that also had people identified on the back, I came to the conclusion that the photographed man is in fact not Roswell Powell as the identified Powell can be seen in other photographs in the collection. I also was able to locate Powell’s picture in the Debris yearbook of 1903 among the other deceased train wreck victims and compared this photograph to one from the Wilmore collection to confirm that they are different people. As the description on the photograph states, the real Roswell Powell did in fact die in the Train Wreck, a fact I found out from news articles and yearbooks that mention the deceased from the wreck. Alongside photographs of the real Roswell Powell, other photographs help to detail Wilmore’s social life with his friends, as all of the photographs include group activities or individual portraits of people that Wilmore would have known during his years at Purdue. Most of the photographs focus on dorm life and show a glimpse into what male social life was like in the dormitories in the early 1900s.

Significance

Social life at Purdue was dominated by men because during the early 1900s, Purdue still had a predominantly male student body. Because of this fact, I find it important to include an object which embodies the standards of masculinity in a school that had a large male population. As I said before, this photograph captures the image of an unidentified man who is posing for a sports photo, and it serves as a solid starting point for the investigation of masculinity both in sports and in other school settings. As historian Kasson states, during the early 1900s there were, “important changes in the popular display of the white male body” (p. 07), and this led to the assessment of “changing standards male strength and beauty” (p. 07) in the representation of men. Other pictures in the collection are similar to the one I picked—although none of them were individual sports photos—which suggests this idea that there was a large, encompassing social push for a man to get a photograph taken of himself in a strong and authoritative posture. Because of all of these aspects, I believe that this photograph will make a great addition to our group investigation of 1903-1904.

Research

The first step for researching this object is to identify if in fact the writing on the back of the picture is Carlton A. Wilmore’s, because if not, I wonder who would misidentify the man in the picture after it had left his possession. I also need to look into pictures of students of the time to identify the man in the photo and then in order to investigate the perceived norms of masculinity of the time, I want to take a look at other pictures of the athletic teams and check the Exponent for any excerpts on the accomplishments of men both in and out of sports to see how people describe the men of the time. Secondary sources that I want to investigate include studies of early twentieth century masculinity.

Blog Entry Two, April 25th 2016

There is Still Hope for This Project

So, I officially feel like a true researcher. By this point, I have read from countless books, (and by “countless”, I mean I’ve read parts of four books), and have formed a pretty good idea of what the turn of the 20th century meant for men and the changing idea of masculinity. It was tough at first to research, I will admit, because I was only really using the internet to find the secondary sources that would help with my researching, but when I realized—and I’m embarrassed at the level of excitement I had at this discovery—that Purdue’s Stewart library has a whole section dedicated to the discussion and research of masculinity, including some books on the time period I’m researching, I greatly accelerated and simplified my research process. A personal favorite, for its content and the way it reads, has continued to be Kasson’s study Houdini, Tarzan and the Perfect Man.

For some reason, however, I have still had absolutely no luck in identifying the figure in my chosen object, because this man is not in any other sports photograph from 1903-1904. Part of me is convinced that he does not actually exist but a more rational side of me is toying with the thought that this man simply graduated before or well after the school year that I’ve been researching, so he isn’t on the football team at the time. I’m not sure if I have to or should spend the time looking for him though. Is it really that important that I put a name to the face of this photograph? I don’t think it will help the overall discussion of this piece and the standards of masculinity of the early 20th century if I do. Nevertheless, this unfound information will haunt me throughout this project. However, while searching for my mysterious football player, I came across many similar photographs that were both athletic and non-athletic. They all shared almost the same composition; a man with a stern face and a confident posture. This commonality made me believe that young men were in fact being influenced by this idea of outwardly manifesting their masculinity through their appearance as some of my corresponding research has suggested. With these ideas in mind, I took a look through the John Miller scrapbook from the Purdue Archives to see if I could find pictures or articles about masculinity, to solidify my hunch of what was influencing the youth, but that ended up being a bust. While the scrapbook was filled with athletics, both pictures and articles, I made the decision that this was less because of any social pressure on this young man to emulate any type of masculinity standard and more related to the fact that he himself was on the football team at Purdue and lived and breathed sports.

On a more fruitful note, I’ve been focusing my time on identifying the major influencers of the early 20th century and have been introduced to Eugene Sandow, the muscle man of the time who almost single-handedly changed the way society perceived the ideal male figure. Sandow was unlike anything that Americans had seen at the time and his large, muscular body became an icon of “the perfect man” for men of the time to strive for. Sandow and others like him made a well-developed, muscular body one of the characteristics of masculinity. (Kasson, 2001).

Along with finding what became the standards of masculinity at the time, I also stumbled upon— actually accidentally in one of my books The Making of Masculinity—a compilation of essays—a reoccurring idea that the standards of masculinity were changed at the turn of the century because “manhood”was being threatened by the growing power and influence of the women in society. Harry Brod attributes men’s sense of inadequacy in their society to, “women’s ill-advised challenge to their traditional role” and “the feminizing clutches of mothers and teachers” (1987).

With men out of the home at their jobs everyday, mothers and other women were left to care for and rear the children, and most importantly, the next generation of men. Even many of the teacher of the time were women, so men began to notice that boys were being exposed to the influences of women rather than men. This was a pressing problem because, as the gentler sex, women were keeping the boys from developing into strong, strapping young men (Kimmel, 1996). So, apparently to combat this horrible problem, men sought to “take back their lost masculinity” by incorporating more outdoor and manly activities into their lives, especially for their sons. Some argue that the Boy Scouts of America was actually set up for this reason and also allowed young boys to have activities of their own, which separated them from the “sissification” caused by playing with girls and encouraged them to lead active lives and even to fight with the other boys regularly (Grant, 2004).

This is the majority of what my research has shown me at this time. As this project progresses, I plan on continuing to read through some more information in my secondary sources, but want to focus on the influences that people had on the men of the time to solidify this new identity of masculinity. Sandow is just the beginning. I think that there may be more, such as John Harvey Kellogg who was referenced in one of my secondary sources and seemed to have some pretty strong ideas of what a man should be.

Blog Entry Three, May 9th 2016

Curtain Call

So, I’m just going to put this out there; I never found out who the man in my photograph is and this saddens me. However, I did find out a plethora of other useful and/or intriguing information along the way—some of which caused me to seriously digress from my chosen topic and simply immerse myself in all that the archive has to offer.

In the final days of my research, I have found that the changes to the standards of masculinity in the twentieth century were not as drastic as I thought they could be, but they definitely did affect the men of the time in many ways. I found that Eugene Sandow, the body-builder, almost single-handedly changed the male image, along with prominent writers and thinkers of the time who also influenced the representation of men.

Now, on to my ideas for writing the final analysis of the topic. I decided to write my final paper on my subject as a straight-forward case study of the photograph from the Purdue Archives. I start the draft by mentioning and describing the photograph itself and then discussing how it could be an example of the way in which men were influenced to change their physical representation at the turn of the twentieth century. I then give background from my research about the actual changes that occurred at the time in order to build my argument that the man in the photograph could in fact be a strong example of the new standards of masculinity that evolved from these social changes. I pull from multiple sources, including my beloved Kasson book, and fill the pages with topics of female influences, questions of sexuality and the emergence of the modern physical development of men. Some of the information, at first glance, seems to be irrelevant, however, I think I do a good job of pulling it all into a single perspective—the best a Biology major can do so far out of her area of expertise. Once the ground work is laid, I bring back the idea of the photograph and discuss my final conclusions of why it is a good case study of the twentieth century’s new standards of masculinity.

This entire project has been a roller coaster for me, with some good days and more than a few bad ones on my quest for archival knowledge! However, I can safely say now that I have learned some valuable lessons on archival research and how to piece together information from many different sources to form a well-rounded analysis. Not only that, but I have thoroughly enjoyed the entire process and think that I, along with my whole honors class, have created a strong and clear picture of Purdue University’s 1903-1904 school year.

Bibliography

To view a working bibliography for this project, click here.

About the Authors:

To find out more about all of the student researchers, click here!

Charlene, your professor recently talked to Purdue University Retiree Association members about her work with the first honors class and how they published their papers in book format and then explained your efforts with this website. It is a wonderful project!

Imagine my surprise when you said the person in the picture was NOT Roswell Powell! My maiden name was Powell, and my father played football when he was young. Of course, he did not attend Purdue University, and he was never in a train crash, so, just like your young man in your picture, this is not his story. Still, masculinity would have been his story in one way or the other.

I think that photography and the evolution of maleness was indeed happening in this period. I found this on the web about one of the leading men of that time in photography and wondered if the Purdue University library might have “Camera Work” in the periodicals collection:

Edward Jean Steichen (March 27, 1879 – March 25, 1973) was a Luxembourgish American photographer, painter, and art gallery and museum curator.

Steichen was the most frequently featured photographer in Alfred Stieglitz’ groundbreaking magazine Camera Work during its run from 1903 to 1917. Together Stieglitz and Steichen opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, which eventually became known as 291 after its address.

This is fascinating! Very eager to hear what else you uncover about the somewhat mysterious photograph and about gender roles/expectations and masculinity during this time period.

I appreciate the author’s approach of using the photograph as a case study to illustrate how these social changes affected the physical representation of men at the turn of the century. It’s clear that a lot of thought and research went into the final paper, and I’m sure it will be a compelling read for anyone interested in the topic.

Overall, I think this article is a great example of the research process and the insights that can be gained from digging deep into archival material. It’s a reminder that even if we don’t find the answers we were looking for, we can still uncover a wealth of information that adds to our understanding of a given topic.