Posted on December 12, 2019 by small20

A Trend of Omission: Student Protest and Activism on Purdue’s Campus

by Max Malavenda

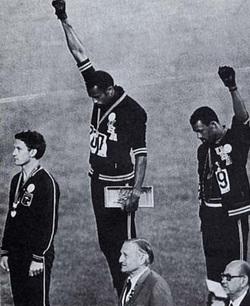

On the 17th of October during the 1968 summer Olympics in Mexico, two black American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, made history when, during the playing of the national anthem, the two men lowered their heads and raised their fists in what is known as the Black Power Salute.[1] Smith raised his right hand as a representation of black power, and Carlos raised his left as a symbol of black unity, with both men wearing black gloves on their raised fists.[2] Smith and Carlos had, only moments before, become the gold and bronze medalists in the Mexico City held Olympic 200-meter race, respectively, with Smith having become the new world-record holder for the event, having completed it in 19.83 seconds. In addition to the salute, the two men also stood on the podium with no shoes but black socks, a symbol of black poverty, with Smith wearing a black scarf around his neck as a symbol of black pride, and Carlos wearing a bead necklace to honor black people who died by lynching in America as well as unzipping his jacket as a show of solidarity with working class Americans, a background Carlos himself came from.[3] In what is now one of the most famous acts of civil protest of racial inequality in the world of sports, Smith and Carlos risked a lot with a seemingly simple gesture intended to raise awareness and inspire. In the immediate aftermath, not only were they two men removed from the Olympic games, they were bombarded with boos from the Olympic crowd, as well as condemnation back home from the media and the public in the form of death threats.[4] The two could not even find universal support within the rest of the United States Olympic team, with the late gold-medal boxer George Foreman stating in regards to their protest, “That’s for college kids. They live in another world.”[5]

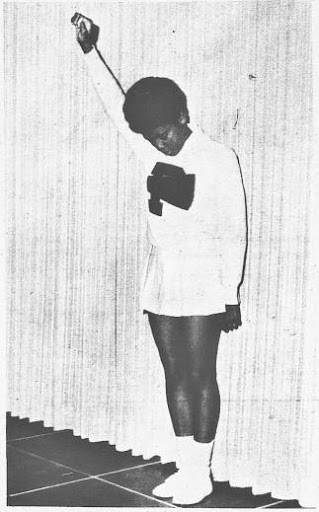

However, as Foreman may have been surprised to learn at the time, such acts were not much easier or without consequence for college students either. One can conclude as much by taking a look at Purdue University’s history with a similar issue. Only nine days after Smith and Carlos’s Olympic protest, two black cheerleaders for Purdue University, Pam King and Pam Ford, began demonstrating the black salute during the national anthem at Purdue’s homecoming football game against Iowa.[6] The resulting controversy surrounding Pam King and the use of the black salute as well as the university’s, more specifically athletic director Guy “Red” Mackey’s response to the protest and other subsequent issues regarding race in Purdue athletics would not only be a blemish on Purdue’s history of its relationship to its minority population, but also serve as a microcosm of racial tensions in the country at large, reflected in events such as the Olympic protest.

Upon King and Ford’s first use of the black salute, they were met with little resistance.[7] As King put it, once their fellow cheerleaders heard their explanation of the meaning of the salute, they, “agreed to allow us to continue if we would make others aware of the explanation.”[8] The explanation of the salute, as King would go on to give similar descriptions many times in the future, was that, “the Black Salute symbolizes the desire to make America a truly free country for all Americans (raised arm, clenched fist) and shame for the racial discrimination that American is now (bowed head).”[9] However, after subsequent uses of the salute by King and Ford, “Red” Mackey openly expressed his distaste for the salute to the captain of the cheerleading squad, and instructed the captain to tell the two not to carry on with it at future games.

To any Purdue student, fan, or local, Mackey should be a familiar name. Guy “Red” Mackey was the athletics director of Purdue University for 29 years, the longest tenure of any Purdue athletic director in history, starting in 1942 and having retired from the position in 1971.[10] However, the average student more likely knows him as the namesake of Mackey Arena, home to Purdue men’s and women’s basketball.

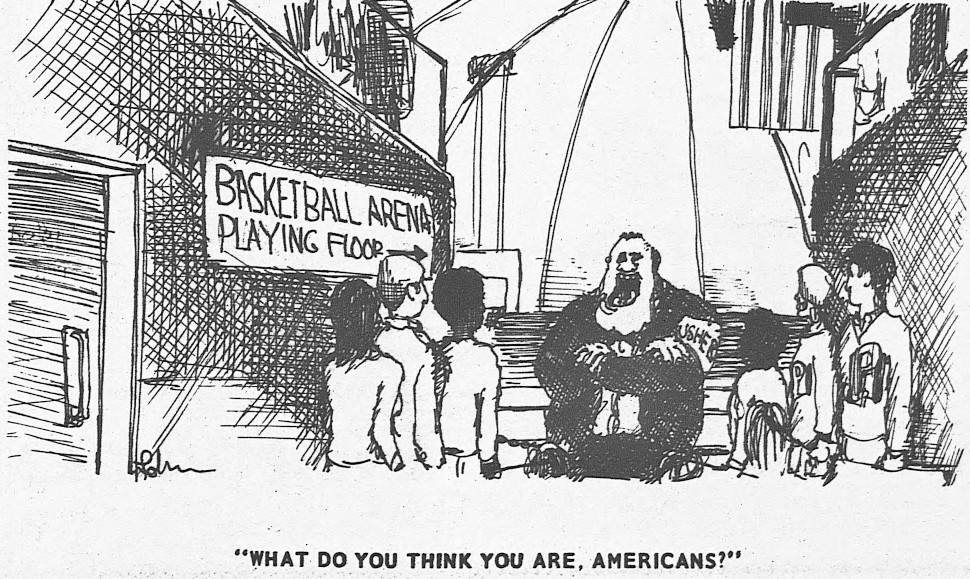

While Pam Ford ceased the black salute for fear of being removed from the cheerleading squad after Mackey made his disapproval known, Pam King went forward with the salute one more time at a home basketball game against North Dakota before both women decided to take the issue to Mackey himself.[11] As King recounted the interaction in an interview with The Exponent, “Mackey told us that he personally disliked the salute . . . but he said the decision was up to the cheerleading squad. He also said that if we were allowed to do the salute then he didn’t know what he would do.”[12] While not a reassuring response, the power to decide seemingly fell upon King, Ford, and their peers. A joint meeting between the cheerleading squad, the pep band, and the pep committee was held, in which it was upheld that King could maintain her position on the team, but that until they could reach a decision on the appropriateness of the black salute at sporting events, the cheerleading squad should remain off the court until after the playing of the national anthem.[13] However, this decision was not one supported by a majority of the cheerleading squad. Thus, in response the cheerleading squad for the following game voted four-to-two for the team to be on the court for the national anthem.[14] Yet, upon attempting to enter the court, the squad was denied access by direct order of Mackey. Upon attempting to reenter in civilian clothes, King was still denied access.[15] After performing as planned for the first half of the game, Pam King turned in her uniform and quit the cheer squad. What would follow were months of back and forth debate in hearing after hearing, leading to an eventual vote on the matter of whether or not King and other black athletes would be allowed to perform the salute.

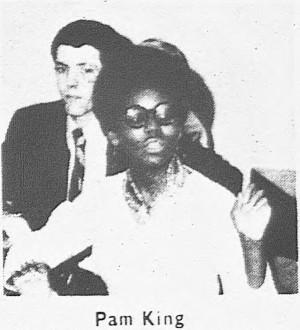

King was no stranger to protest and activism on her campus and community and would continue to be involved in such issues. She advocated for things such as the increased inclusion of blacks in the history of Purdue.[16] Simultaneous to the controversy surrounding her and the Black Salute she was also filing a formal complaint with the Lafayette Human Relations Committee against Gerald Clark, the principal of Sunnyside Junior High School, on the grounds of racial discrimination after Clark cancelled a scheduled speaking engagement King had at the school on “Black Power and Black History” because the subject was, “too touchy.”[17]

Even King’s position on the cheerleading squad was a point of controversy. In May 1968, the Black Student Action Committee, of which King was the activities chairman, had pressured the athletics department to accept two black cheerleaders to the squad for the upcoming academic year[18], those cheerleaders being King and Ford.[19] In the hearings following her barring from the basketball game, King would cite this integration as a point of contention between her and her white squad mates, who thought by letting them on the squad, “they had done the blacks a favor . . . therefore they felt we owed them the favor not to do the salute,” King said.[20

Beginning in January 1969, the hearings were to last until February 17th, on which date the committee would vote on a proposed resolution.[21] During this time, even Frederick Hovde, president of the university at the time, spoke out against the salute, claiming not to know its meaning (King had only weeks prior to this statement explained the meaning personally to Hovde).[22] In the hearings led by a joint committee of the student senate leading up to the vote, while Mackey was invited to initial meetings, he was not invited to the later meetings. While he complained publicly about not being invited, saying he would be happy to attend, the student senate claimed they ceased to invite him because he indicated the exact opposite, that he would not be attending any hearings on the matter.[23] Luckily, Mackey’s involvement did not appear to be crucial, as on February 17th, a resolution was passed by a unanimous vote. The resolution stated, “The university should assume no official position on the Black Salute. In particular, this expression does not furnish sufficient grounds for direct or indirect disciplinary action by university students, faculty, staff, or administrative voices.”

While the passing of the resolution was undeniably a success for King as well as the black student body at large, one would be hard pressed to trace any tangible change it caused. Mackey and the Purdue Athletics department would go on to have a continuously spotty record with black athletes for the remainder of 1969. In the weeks after the resolution vote, Pam King was supposedly the only former cheerleader not invited to a cheerleading banquet, rumored to be at the request of Mackey.[24] However, the event is still significant and unique when compared to other controversies surrounding Purdue’s black student body. First, this is one of the only major instances involving black students where a woman was both at the center of the issue and the forefront of combating it.

As one pushes through Purdue’s history of such events, even all the way to contemporary times, these parallels, both positive and negative, continue to exist. One such parallel can be drawn between the rhetoric of the current United States president, Donald Trump, and the various administrations of Purdue University. The date is August 15, 2017 and the forty-fifth president of the United States, Donald Trump, says at a press conference that there are, “some very fine people on both sides.” The “two sides” in question refers to the clash of white nationalist, Unite the Right protesters, who were demonstrating against the removal of a statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, and the counter-protesters who formed in response. The President was criticized widely for his remarks on the event, which led to the killing of counter-protester Heather Heyer after she was run over by white nationalist protester James Fields. As Washington Post reporter Aaron Blake put it at the time, “Trump does this a lot. He will say something suggestive — in this case, suggestive that the violence in Charlottesville wasn’t really such a clear-cut result of resurgent racism — and then he will later say something else to give himself plausible deniability.”[25]

This type of vague, plausible deniability is not unique to the president, and on some occasions can be found much closer to home than expected. We even can find examples of this when looking at our own Purdue University. Just in the past month (November 2019), Purdue student Jose Guzman Payano, a resident of Puerto Rico and U.S. citizen, was denied access to mucinex by the CVS clerk because they did not believe he was providing the required U.S. identification to do so (Payano had presented his Puerto Rican driver’s license as well as his U.S. passport and was still denied the medication).[26] Sitting university president Mitch Daniels has been criticized for his initial lack of and later refusal to comment on the incident. This silence is surprisingly characteristic of how Purdue’s presidents have dealt with similar issues of race and discimination. In this piece, I will continue to explore this complacency through silence as it occurred at Purdue University and relates to dialogues occurring on a national level, as well as highlighting those who challenge this complacency.

The instance regarding Jose Guzman Payano would not be the first time president Daniels himself has been criticized for his lack of a stance on similar issues. In 2016, unidentified persons left about half a dozen posters in the Stanley Coulter Building that conveyed white supremacist messages. The posters were courtesy of white supremacist website American Vanguard (now known as Vanguard America), a group that James Fields identified with, and said things such as, “We Have A Right To Exist,” and, “White Guilt: Free Yourself From Cultural Marxism.” Additionally, the American Vanguard Twitter account suggested that the act was perpetrated by students of Purdue University.[27] This came quick on the heels of a similar incident two months prior, in which a separate white supremacist group, Identity Evropa, left posters of theirs around campus. However, when asked to make statements condemning these posters on both occasions, Daniels decided it would be in the University’s as well as the student’s best interests if a comment were not made, as to not draw attention to the groups in question. In reference to the posters, Daniels said “This is a transparent effort to bait people into overreacting, thereby giving a minuscule fringe group attention it does not deserve, and that we decline to do.”[28]

Similar silence can be observed in the years 1968 and 1969 during a string of controversies Purdue’s athletic department encountered with black student athletes. In the span of a few months, the university would face backlash for not permitting a black cheerleader to do the black power salute during the national anthem, two black track athletes were not permitted to run on account of their mustaches,[29] and another black track athlete was denied his varsity letter that by his account he had earned and claimed it was on racial grounds he was denied it.[30] In all of these instances, the president at the time, Frederick Hovde, either remained neutral on the matters and deferred to the head of athletics at the time, Guy “Red” Mackey, or in some cases feigned lack of knowledge of the incidents.

Not all Purdue administrations have been so reluctant to meet the needs and requests of Purdue’s black student community. In 2005 Purdue planned to name an auditorium in Pfendler Hall after Earl Butz, former Dean of Agriculture and the Dean of Education at Purdue as well as the Secretary of Agriculture under President Richard Nixon, after Butz gave a one-million dollar donation to the university.[31] However, Butz is more infamously known for a racist and particularly profane remark made in August 1976 in the company of Sonny Bono, Pat Boone, and White House Counsel John Dean.[32] In response, 70 students arrived at Hovde Hall to protest, among other things, the dedication of the auditorium in Butz’s name in an attempt to convince university president Martin Jischke to reconsider. In a rare instance of response from the University, they decided to instead name the auditorium the Deans of Agriculture Auditorium. However, even in this moment of success on behalf of student protestors, the decision was only made by the university after agreement from Butz, who framed the issue as freeing, “Dr. Butz and his immediate family from an issue that has become very difficult for them.”[33]

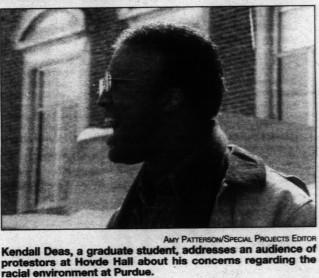

President Steven Beering is also not free from this trend. In 1999 Kendall Deas, a graduate student in the political science program, was expelled from Purdue when he was accused of academic dishonesty. This accusation came on the heels of Deas accusing a professor of his of using racist language against him in the classroom, something that was confirmed by two review panels, which unfortunately led to little action being taken by the university against the professor in question. This led Deas and many other students to believe that his expulsion had to do with this instance of racial discrimination, leading for multiple large student protests which attempted to deliver letters to President Beering. However, on both occasions of protest, President Beering declined to appear, and outside of those events made little comment on the matter.[34]

When beginning to not only analyze the events and their subsequent responses, it is also important to analyze who is leading the charge in looking for a response from the university. Of the examples given here that there is documentation for those challenging the university, there is a trend of black female students being the lead organizers for change. Drawing on the very first example, Pam King was an early and important figure in this regard. King is also unique in that among similar cases involving the Purdue athletics department, she is the only one at the time who would continue not only to be involved in the fight, but to be the main force by which the fight was fought. In comparison to her male counterparts at the time who clashed with Mackey and the athletic department, two black athletes prevented from running at the time due to their having mustaches and another who was prevented from receiving his varsity letter when by most accounts he qualified, all of whom were on the track team, none of them pushed the issue any further than the initial incident and subsequent reporting. If there was any pushback, it was not led by the athletes themselves, but by other relevant organizations such as the Black Student Union.

In regards to the Deas incident, while he was involved heavily in the protests regarding his expulsion, the protests were largely organized by the Black Student Union, whose leadership at the time was largely female. Articles from the time attribute the organizing to people such as Nicole Jefferson, the fundraising coordinator at the time, and Aisha Washington, the vice president of the black student union at the time.[35] This organization by women in the BSU is echoed in the more contemporary issues on campus, as one of the leaders of the current movement surrounding Jose Guzman Payano is D’Yan Berry, current president of the Black Student Union.[36]

However, while Pam King was the earliest example of this female driven activism, is not without its feminist critique. The most significant of which I would like to point out is King’s referring to the salute as the, “Black Man’s Salute.” While, when reading her thoughts on and meaning behind the salute and the issues facing black citizens, it may be clear that she is speaking of both black men and women, King is engaging in rhetoric that often leads to the exclusion of black women from movements of social change and political reform. Whether intentionally or not, this historic exclusion of black women from both the civil rights movement, with black men gaining the right to vote long before black women, as well as the feminist movement, with some of its origins tarnished by racism, is mirrored in King’s language when discussing the issue. In this way and in addition to the parallels between Pam King and Olympic athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith, we have another, less positive, reflection of Purdue culture contributing to the omission of black women from some of the most significant cultural movements of our country’s history.

[1] “1968: Black Athletes Make Silent Protest.” BBC News. BBC, October 17, 1968. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/17/newsid_3535000/3535348.stm.

[2] “1968: Black Athletes Make Silent Protest.”

[3] Boykoff, Jules. “Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and the 1968 Olympics: 50 Years Later.” Versobooks.com, October 16, 2018. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4088-tommie-smith-john-carlos-and-the-1968-olympics-50-years-later.

[4] Boykoff, Jules. “Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and the 1968 Olympics.”

[5] Ibid

[6] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” The Purdue Exponent, December 19, 1968, Vol. 84, No. 67, 3.

[7] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” 3.

[8] Ibid, 3.

[9] Ibid, 5.

[10] Purdue University Athletics. “Remembering Red,” Purdue University Athletics. Purdue University Athletics, December 2, 2017. https://purduesports.com/news/2017/12/2/Remembering_Red/.

[11] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” 3.

[12] Ibid, 3.

[13] Ibid, 5.

[14] Ibid, 5.

[15] “Who Wants An Anthem?” The Purdue Exponent, December 16, 1968, Vol. 84, No. 64, 5.

[16] Paul J. Buser, “’Progressive’ Faculty?” The Purdue Exponent, May 16, 1968, Vol. 83, No. 137, 11.

[17] Kathie Barnes, “Formal Complaint Filed Against School Principal,” The Purdue Exponent, March 4, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 90, 1.

[18] Kent Hannon, “There Comes A Time,” The Purdue Exponent, May 23, 1968, Vol. 83, No. 142, 16.

[19] “Purdue Gets Two Negro Cheerleaders,” The Purdue Exponent, May 23, 1968, Vol. 83, No. 142, 16.

[20] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” 5.

[21] Meg Lundstrom, “Cheerleader’s Black Salute Becomes Issue Again,” The Purdue Exponent, February 7, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 73, 10.

[22] “We’d Like To Say Hooray,” The Purdue Exponent, December 19, 1968, Vol. 84, No. 67, 8.

[23] Bob Metzger, “Mackey Not Invited; More Talks Planned,” The Purdue Exponent, February 11, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 75, 1.

[24] Larry Venderhoeff, “Makcey-King Battle Takes Another Step,” The Purdue Exponent, December 26, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 86, 5.

[25] Aaron Blake, “Trump tries to re-write his own history on Charlottesville and ‘both sides’,” The Washington Post, April 26, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/25/ meet-trump-charlottesville-truthers/.

[26] Karen Campbell, “Purdue student denied medication from CVS, questioned on his immigration status,” WTHR, November 6, 2019, https://www.wthr.com/article/purdue-student- denied-medication-cvs-questioned-his-immigration-status.

[27] Dave Bangert, “Bangert: Faceless supremacists at Purdue,” Journal & Courier, November 30, 2016, https://www.jconline.com/story/opinion/columnists/dave-bangert/2016/11/30/bangert- nameless-faceless-supremacists-purdue/94682330/.

[28] Meghan Holden, “White supremacist group posts fliers at Purdue,” Journal & Courier, September 18, 2017, https://www.jconline.com/story/news/college/2017/09/18/white- supremacist-group-boasts-poster-campaign-purdue/678478001/.

[29] Steve Pollyea, “‘Red’ And The Black,” The Purdue Exponent, April 15, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 114, 15.

[30] Stephanie Salter, “Jones Charges Possible Racism,” The Purdue Exponent, March 13, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 97, 1.

[31] Warren Mills, “Purdue removes Butz’s name from lecture hall,” WTHR, August 1, 2005, https://www.wthr.com/article/purdue-removes-butzs-name-from-lecture-hall.

[32] When asked why his party, the Republican party, was not able to attract more black voters, Butz replied, “I’ll tell you what the coloreds want. It’s three things: first, a tight pussy; second, loose shoes; and third, a warm place to shit.” Eugene S. Robinson, “The Earl Butz End Of A ‘Joke,’” Ozy, February 11, 2018, https://www.ozy.com/flashback/the-earl-butz-end-of-a-joke/83773/.

[33] Warren Mills, “Purdue removes Butz’s name from lecture hall,”

[34] Carly Maitlen, “Protest raises racism issues,” The Purdue Exponent, March 11, 1999, Vol. 155, No. 44, 1.

[35] Ibid., 2.

[36] Anna Darling, “People Gather At Town Hall Meeting To Discuss Discrimination At Purdue,” WTHR, November 11, 2019, https://www.wlfi.com/content/news/People-gather-at-town-hall- meeting-to-discuss-discrimination-at-Purdue-564783642.html.

[37] Tommie Smith and John Carlos making black salute at 1968 Olympics, “Poignant Moments In HISTORY.” eBaumsWorld, November 7, 2012. https://www.ebaumsworld.com/pictures/poignant- moments-in-history/82653187/.

[38] Pam King making black salute, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 142, 5.

[39] Cartoon depicting the cheerleaders bar from entry during national anthem, 1968, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 64, 5.

[40] Pam King attending attending Lafayette HRC hearing, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 90, 1.

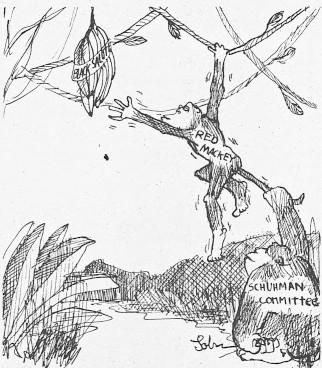

[41] Purdue Exponent cartoon depicting Red Mackey being stopped from touching the Black Salute by the Schuman Committee resolution, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 79, 8.

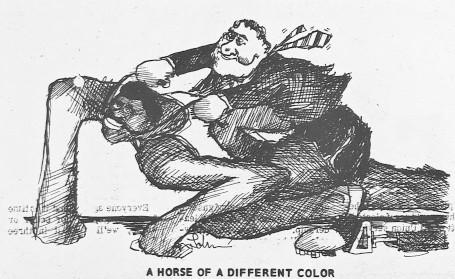

[42] Purdue Exponent cartoon depicting Red Mackey riding a black track athlete by their mustache, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 113, 8.

[43] Kendall Deas addressing protestors, 1999, The Purdue Exponent, March 11, 199, Vol. 155, No. 44, 1.

Banner Image Reference in bold.