Posted on November 19, 2019 by small20

Women on Campus: Memories of Purdue’s Campus & Classrooms in the Seventies

by Anna Brown

“Being sensitive of institutional inequality was not on my radar screen, everyone was treated fairly. It became clearer and clearer that was not the case.” (1) Betty Nelson joined Purdue University staff in the mid-1960s with this mindset as many female students did. As the decade closed and the seventies began, the wall of inequality began to break down for many women on Purdue University’s campus as the modern woman developed. Over the course of several interviews, it is apparent that inequality struggles were not across the board. Women in nursing or other predominantly female fields of study did not encounter the same situation in class as women in predominantly male fields. Additionally, there were still overarching gender stereotypes that all women faced, regardless of their degree and career.

The classroom is one of the clearest ways to grasp whether women struggled with bias based on their gender or if they were treated the same as their male counterparts. Teresa Roche, a Purdue student from 1974-1979 spoke of the composition of her classes. As a secondary education and interpersonal & public communication major, her liberal arts classes were mixed, but dominantly female. (2) Similarly for Barbara MacDougall, a woman who pursued and received a nursing degree from Purdue from 1970-1974, her nursing classes were “One hundred percent female. There were no men.”(3) However, for the women who stepped outside of the more traditional degree paths like Laurie Roselle, a political science major, and Julie Wainwright, a general management major, this was not the case. Julie Wainwright went to class with “mostly males” and Laurie Roselle remembered the compositions of her political science classes as being heavily male.(4) Roselle remembers “walking into one 500 level course and being the only woman in it.”(5)

It was not just the student composition in classes that were unequal, but women professors, outside of predominantly female fields like nursing, were few in number. MacDougall remembers her nursing classes as taught by one hundred percent female professors, but the science classes required for her major were all taught by male professors.(6) Roselle and Wainwright alike did not recall even one female professor that they could recall from their time at Purdue.(7)Although the inequality of men and women professors was apparent, the women interviewed spoke highly of their male professors. Laurie Roselle was the only female in one of her major-related classes, however, her male professor, upon noticing Roselle, pulled her aside and said, “I saw your face when you walked in, you are not dropping this class.” Roselle remembered, “He took the time to talk to me and told me, ‘You bring a different level of conversation to this seminar class.’”(8) This action encouraged Roselle in her education, both in her undergraduate and graduate studies. Julie Wainwright had a significant positive experience with a professor and a lasting negative experience with a teaching assistant in her class. Julie recalled her notably positive experience: “We had a visiting professor from Harvard, he was teaching consumer psychology. I did so well on a test he asked to meet me. He said he had never seen someone do so well and placed calls with companies I wanted to work for.”(9) On the flipside of that account, Wainwright experienced blatant, public, and uncalled for sexism from a teaching assistant who responded to her high grade. The teaching assistant “accused me of cheating on a test. He said, ‘I couldn’t look like I do and be smart.’ He said it in front of the whole class.”(10) These situations were, as Wainwright put it, “diametrically opposed.”(11) Regarding the first situation, Julie stated that the professor “Didn’t see gender,” but the teaching assistant, “Couldn’t get past it.”(12) Whereas some students experienced direct positive or negative remarks and treatment from professors, Angie Klink gave different insight into being a female in a predominantly male classes. After she successfully completed a final project in a unique way, Klink received no encouragement or remarks from her male professor. “Silence can also do damage,”(13) Klink reflected back on that experience. The failure to vocally recognize the success of women spoke volumes to students like Angie. The Purdue Exponent published an article in 1972 that highlighted the conflict women on campus experienced, in the classroom and after graduation and confirms Klink’s memory. Regarding individuality of women in the classroom, the female author wrote: “In many situations, the problem arises that when a man stands up and argues intelligently, he is considered quite a guy but when a woman does it she’s called an “aggressive bitch.” Unfortunately, there are usually unspoken rules as to how a woman is expected to act. That is what tears some women up– to listen to what’s expected of them and at the same time have their own ideas deep inside as to how they would like to act.”(14)

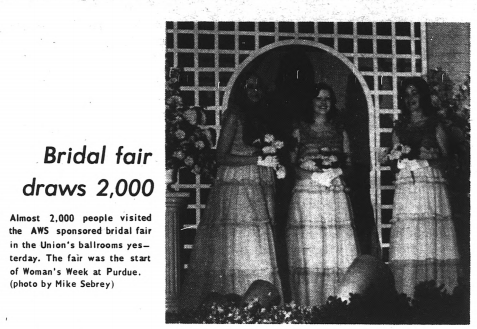

The classroom was not the only setting in which bias existed towards female students. Teresa Roche was a very involved student at Purdue, a member of several organizations where she felt equality did exist. However Roche did say what she felt needed to change within the dominant women’s organization on campus, the Association for Women Students. The organization held one main event each year for women, a spring bridal fair.

This event for Roche caused her to be “Unbelievably struck by what was conscious and unconscious bias.”(15) Betty Nelson noted Roche was a part of a new era of women in the association who believed, “We can do more if we change our programming.” Purdue was the last school in the Big Ten conference to sponsor a bridal fair which was as Nelson phrased, “Fun, fluffy, and a good leadership experience.”(16) However, Roche and Nelson both understood that the underlying message of the main women’s event of the year being a bridal fair emphasized that women should be engaged by the time they graduated.(17) This idea called into question the purpose of women going to college, whether it was to further their education or to become a bride. Betty Nelson had previously recognized the need to shift away from the bridal fair but she “felt like students needed to be the ones to say we were ready to move on.”(18) The seventies proved to be the era in which students were ready to move on from these stereotypical and gender biased kinds of events.

Gender inequality was shifting further towards equality in the seventies. Title IX was passed in 1972(19) in order to create equality and prevent discrimination for women in federally funded programs, including athletics. This was a major breakthrough for women. However, Barbara MacDougall emphasized that the inequality of opportunity in sports did not even occur to her because, “In high school, there were no sports for females. I could participate in intramurals but no teams.” So when she was in college, “It wasn’t like I was a great athlete in high school and then didn’t have an opportunity. No one had an opportunity.”(20) The effects of a major legislative victory like Title IX were not felt in a dramatic way by Barbara MacDougall and her friends because the inequality was so normalized. The desire to have equal opportunity with men in the athletic realm had not crossed many women’s minds. Teresa Roche on the other hand, was quite cognizant of women’s issues during her years at Purdue. Therefore she saw that Title IX was not being completely enacted on Purdue’s campus.(21) According to Teresa, “Things had not reached any sense of equality or equity when I was involved with women’s issues.”(22)

In the seventies at Purdue it was evident that women challenged the status quo and pursued degrees in male-dominated spheres. Each woman interviewed recounted at least one professor who did not see gender and encouraged their pursuits. Regarding inequality as a whole for American women, Julie Wainwright believes that “Purdue can’t be tarred with the same brush.”(23) It is noteworthy that women at Purdue were given opportunities, encouragement, and respect by at least some of their male peers and professors. But it is also undeniable based on accounts given by these women that there was gender bias, inequality, and struggles these women grappled with during their years on campus.

- Betty Nelson, telephone interview by author, October 18, 2019.

- Teresa Roche, telephone interview by author, October 4, 2019.

- Barbara McDougall, telephone interview by author, October 15, 2019.

- Barbara McDougall, telephone interview by author, October 15, 2019.

- Laurie Roselle, telephone interview by author, October 11, 2019.

- Laurie Roselle, telephone interview by author, October 11, 2019.

- Barbara McDougall, telephone interview by author, October 15, 2019.

- Laurie Roselle, telephone interview by author, October 11, 2019.

- Laurie Roselle, telephone interview by author, October 11, 2019.

- Julie Wainwright, telephone interview by author, October 29, 2019.

- Julie Wainwright, telephone interview by author, October 29, 2019.

- Julie Wainwright, telephone interview by author, October 29, 2019.

- Julie Wainwright, telephone interview by author, October, 29, 2019.

- Angie Klink, telephone interview by author, October 10, 2019.

- Marlene Carlos, “Women Who Seek Success,” The Purdue Exponent, September 13, 1972, Vol. 88, No. 12, 5.

- Teresa Roche, telephone interview by author, October 4, 2019.

- Betty Nelson, telephone interview by author, October 18, 2019.

- Teresa Roche, telephone interview by author, October 4, 2019.

- Betty Nelson, telephone interview by author, October 18, 2019.

- Title IX

- Barbara McDougall, telephone interview by author, October 15, 2019.

- Teresa Roche, telephone interview by author, October 18, 2019.

- Teresa Roche, telephone interview by author, October 18, 2019.

- Julie Wainwright, telephone interview by author, October 29, 2019.

Banner Image Reference: The Purdue Exponent, February 10, 1972, Vol. 87, No. 75, 11.

Category: Women’s Place at Purdue, 1960-1990 Tags: 1970s, gender inequality, inequality, Women in the classroom