Posted on November 14, 2019 by small20

Home Economics and the Practice House

by Anna Brown

“If you are a young woman and want to get married, a college or university campus is the best possible hunting preserve. Such a campus is well stocked with young bachelors who are already on their way up because they have taken the pains at least to begin a college education.” (1) This quote, printed in the Purdue Exponent in 1963, depicts the assumptions and beliefs of American society regarding women and education in the sixties. The content of the campus and local newspapers reveal the expectations and molds women were to fulfill. The imagery of a hunter chasing prey is a colorful illustration that insinuates the only reason for a woman to attend college was to find a husband. The sixties decade started with the culture questioning whether or not a woman’s education was valuable and worthwhile investment. The sixties decade ended with movements of liberation and parietal rules ending.

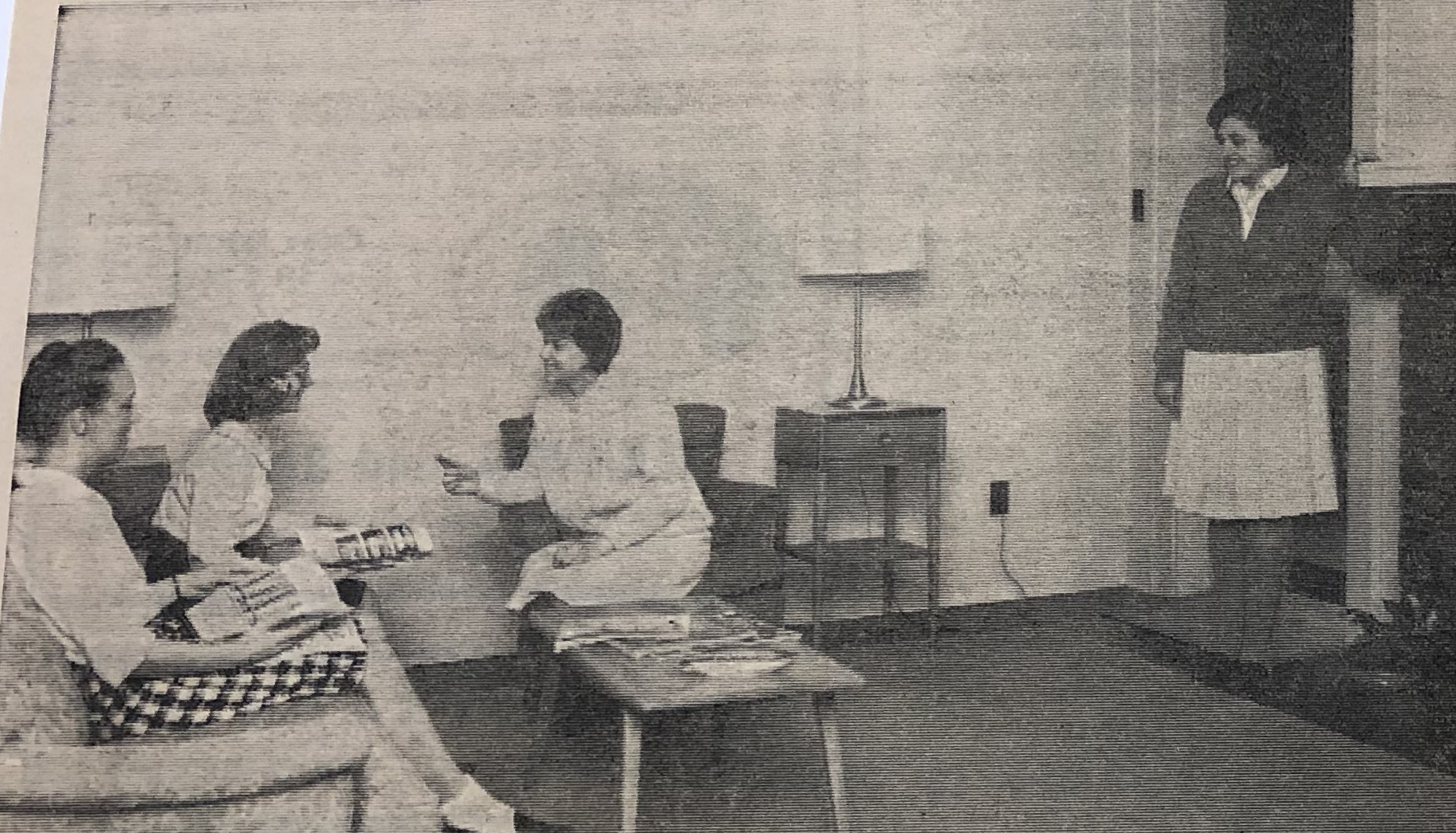

Public universities began enrolling women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, but the mundane degrees offered confined many young women into the role of home-economics teacher or homemaker. Purdue University enrolled their first female student in 1875. (2) For women pursuing a higher education during this time in a coed university, the education came with apprehension, etiquette books, and at Purdue, the “practice house.”(3) The College of Home Economics at Purdue University encompassed the education considered necessary for women to become proficient housewives, home-economics teachers, fashion designers, workers in food preparation, and nursery school teachers.(4) This kind of education molded women into the roles that society expected of them. The “practice house” or Purdue’s Home Management house was a facility designed to test the domestic skills of senior women in the home economics program. One of the requirements for a woman to receive a degree in home economics was to spend six weeks keeping house in one of the four practice house facilities.(5) During their six-week stay, the group of women lived in the practice house and were tested on their abilities in “following a budget, managing laundry, keeping house, and preparing and serving meals,” according to a newspaper article written in 1964 describing the program.(6) Even halfway through what is commonly believed to be a more progressive era for women’s rights, this emphasis on domestic skills was still a common education for women. An article published in 1962 described the College of Home Economics emphasis in the integration of men into the College of Home Economics and the degrees they could receive.(7) Unsurprisingly, men were not receiving degrees that prepared them for life as a housekeeper, but degrees like nutrition, dietetics, and management. Therefore the practice house was strictly for measuring a woman’s proficiency in domestic skills. Women were given the option to receive more nontraditional degrees that focused on the management side to consumerism, but the option did not go both ways. Men were not being tested in the practice house.

The nineteen sixties was not a decade when norms for women completely changed but it was the era that initiated the beginning of change. Many women in this era still followed the predictable route of attending college in order to meet husbands and receive an education that prepared them for keeping house and raising children. The goal of domestic happiness was still pursued by most women during this decade. However, women intending to pursue goals outside of this sphere, had many prejudices, discriminatory rules, and glass ceilings to shatter. Women attending Purdue were no exception. One social sphere at Purdue that promoted the cultivation of women within the academic and social setting was the sorority. The Purdue Exponent published an article in October 1965 titled, “Sociologist Explains Problems Facing Sorority’s Existence.”(8) The author expressed concern and the problems that sorority women faced. “But the worst blow of all to the sorority system comes from the effect of increased academic pressure on the dating habits of college men. Academic competition on most campuses is keen and college men no longer have time for the form of courtship that made sororities so exciting. When parents find that sorority membership does their daughter little good, the system as we know it will go into history.”(9) This “concern” had many implications. First, it implied that the fundamental and main purpose of sororities were to congregate eligible women to meet eligible bachelors that were fraternity members. According to this author, without the viability of interested men as suitors, parents would not find sororities a worthwhile investment for their daughters. However, forty-five years later, Barbara Macdougall and her friends, who still vacation together each year, attest to the lifelong friendships, academic encouragement, and involvement in community service as reasons why sorority living was worthwhile.(10) Going even further, the author of this article really questioned the purpose of women on a college campus outside of pursuing a husband.

A different article published in the Purdue Exponent asked and answered the question of what was the purpose of a woman’s higher education. Published in 1963, “Why do Women go to College,” the male author introduced the article by stating, “The girl who tells us she is going to college only to get an education is simply giving the acceptable answer, but it isn’t the right one.”(11) This author proceeded to argue that an education was unnecessary for women because most college-educated women became stay-at-home wives and mothers. “’The root of discontent in American women is that they’re too well educated. They do not need college education.”(12) Their education, he argued, was the reason for their apparent discontentment. According to the author, women could be satisfied with a basic education with an emphasis on domestic skills. Anything more than that bred discontent. He concluded the article by writing that education itself does not breed “wifely discontent” but an unused education does.(13) “Education is dangerous for women only when they don’t use it. All over America we have women college graduates who are contributing to the betterment of the communities they live in. They start co-operative nurseries; they spark the local educational systems; they innovate new cultural programs; they use their education to make life better for their husbands, children, neighbors—in fact, for the entire nation.”(14) This ideology on a woman’s education was published in the Purdue Exponent and read by both male and female Purdue students. It revealed the kinds of barriers women would overcome. Societal expectations in the early sixties affected a woman’s academic experience. Culture designated their role to become women who would use their education in ways that improved the lives of their children, husbands, and community. Becoming CEOs, business owners, or politicians was not in this role. It is pivotal to understand the challenges Purdue women faced as they entered the university setting in the early sixties. Change was not automatic, but slowly achieved.

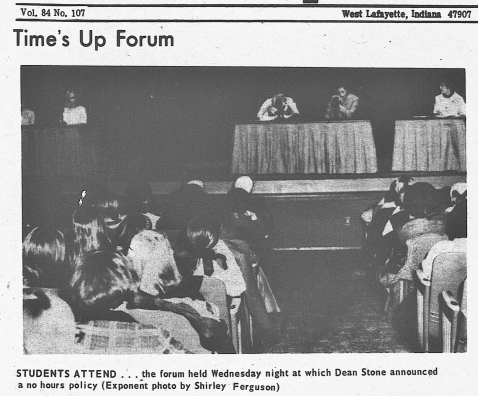

The end of the sixties showed remarkable differences from its beginning. It was not until 1969 that Purdue removed the “women’s hours” 10:30 p.m. curfew imposed on its female students. (15) This rule was a part of the “parietal rules,” or rules that regulated when women could come and go from dormitories, where they spent time, chaperonages, and any other rules that were women-specific. (16) The end of the sixties brought an era of transition from the traditional domestic role to the career woman. Even the language of the Purdue Exponent reflects this transitional time. Rather than articles that questioned the reasoning and validity of women’s existence and education at the college level, articles discussed anti sex-discrimination groups and liberation movements (17), sexual liberation of the college woman (18), and the change of parietal rules. According to an article in the Exponent that discussed the women’s movements at Purdue, “The women’s liberation movement at Purdue is part of a national movement which is trying to end the “degradation, slavery and discrimination” felt by the modern woman.”(19) This kind of article clearly outlines a dramatic shift from the articles written in the earlier half of the decade. The language and content of the Purdue Exponent reflects the changes that had already occurred on Purdue’s campus. Women were beginning to step out of their formerly designated career as a homemaker and stepping into the seventies, an era that brought women closer to equal opportunity and shaped the modern woman.

- Lloyd Shearer, “Why Do Women go to College,” The Purdue Exponent, November 7, 1963, Vol. 79, No. 37, 3.

- John Norberg, Ever True: 150 Years of Giant Leaps at Purdue University (West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 2019), 86

- Lynn Peril, College Girls: Bluestockings, Sex Kittens, and Coeds, Then and Now (New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2006), 95.

- September 16, 1958 newspaper from Purdue archives.

- “Practice What They’ve Learned,” The Journal and Courier, Lafayette, Indiana, December 12, 1964, 6.

- “Practice What They’ve Learned,” The Journal and Courier, 6.

- Mary Ellen Rosenthal, “Future Bright for 40 Males in Purdue Home Ec School,” The Journal and Courier, Lafayette, Indiana, December 13, 1962.

- “Sociologist Explains Problems Facing Sorority Existence,” The Purdue Exponent, October 28, 1965, Vol. 81, No. 32, 6.

- Ibid.

- Barbara MacDougall, Kathryn Nagel, Betsy Miely, Susan Maddox, telephone interview by author, October 15, 2019.

- Lloyd Shearer, “Why Do Women,” 3.

- Ibid, 3.

- Ibid, 5.

- Ibid, 5.

- Norberg, Ever True, 241.

- Peril, College Girls, 149.

- “Campus Movement Campaigns to Halt Sex Discrimination,” The Purdue Exponent, March 6, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 92, 2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Banner Image Reference: Senior Women living at the Practice House: Journal and Courier, Lafayette, Indiana.