Posted on November 5, 2019 by small20

Betty Nelson: Sleuthing in Bluefield

by Anna Szolwinski

Dean Betty Nelson has come to be one of the most highly respected figures in Purdue history. Known for being an “iron fist in a velvet glove,” Betty pioneered the fight for the disabled and contributed to the revolution for women’s rights during her time at Purdue. Female students such as Teresa Roche and Jane Hamblin revere Betty for her commitment to furthering the status of women on campus and leaving behind a legacy of female empowerment. Although Betty was privileged to grow up in a loving household and receive a college education, her confidence in her female identity was primarily a result of observational learning rather than direct influence. Despite the lack of strong female role models during her childhood, Betty “was on [her] way to being a feminist and didn’t even know the terminology.”(1)

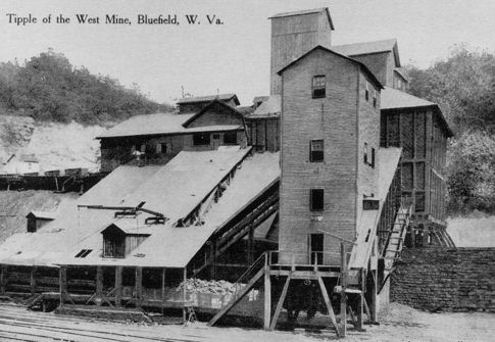

Betty Rebecca Mitchell was born in Bluefield, West Virginia to Emory and Margaret Mitchell. Bluefield’s economy was centered around the coal mines, which lay buried underneath the town. Noises of bellowing train horns echoed throughout Bluefield as coal was transported to companies and families across America.

Betty’s father, Emory. P Mitchell, was Bluefield city manager, while her mother, Margaret Mitchell, was a stay-at-home mom. The Mitchell family preached strong traditional values, including honesty, integrity, and usefulness. Although Betty was born second, the 10-year difference between her and her brother Lewis allowed Betty to mature into a “functional first.”(2) Rather than be overshadowed by her older male sibling, Betty learned to adapt to the role of the first child and explore her independence.

Betty first began to learn about inequality in American society through her experience in elementary school, a time during which she was exposed to a full range of socioeconomic classes and backgrounds. When asked about her class, Betty laughed and said it was the most “rag-tag group you have ever seen.”(3) Crossed-eyes, stringy hair, and face acne were among the qualities that characterized Betty’s classmates. One student in particular, Arthur, stuck in Betty’s mind. He often missed class, which caused Betty to wonder how someone could so frequently not come to school. Later, Betty learned that Arthur was only able to attend class when it was his turn to wear the shoes.(4) Experiences like these enabled Betty to learn about a wide range of people from a young age and “grow up with compassion and understanding as a responsible adult.”(5) Betty’s elementary years were also a time during which she was exposed to the discrepancies in the treatment of genders. She noticed that her mother would pack her brother’s lunch but not her own, and at this moment, Betty knew that “males and females were valued differently in our society, and [she] didn’t think that was rational.”(6) Although she was never explicitly taught about the American values, Betty’s observational learning allowed her to understand the process of marginalization and discrimination from a very young age.

The gender roles within the Mitchell family were reflective of the era during which Betty grew up, a time when women’s sole purpose was to raise children, support the household, and please their husbands. Betty was taught that women were seen and not heard, which was further exemplified by the female role models in her life. Betty’s mother had been a teacher prior to getting married and spent little time outside of the home after having children. Similarly, Betty’s other female influences subscribed to the societal norms of the time. Her friend’s mother was a teacher, her neighbor was an executive secretary, and her cousin was a surgical nurse. When asked about her role models, Betty astutely stated:

“Nobody has to tell you something if you see examples like that; all really good people, and I’m sure they grew up a little bit like Jane Austen’s women [believing that] if you grow up and attach yourself to somebody he will take care of you…I learned that isn’t necessarily going to happen.”(7)

Betty’s determination to function independently in society could be attributed to the strong female role models she encountered in literature. An avid reader of Nancy Drew novels, Betty learned that women could have their own aspirations outside of fulfilling a man’s requests. As she read under the covers with a flashlight, Betty learned that “Nancy was different. She was an independent thinker, good at analyzing situations, willing to step beyond some of those boundaries most women were afraid to approach. She didn’t wait around for Ned [Nancy’s special friend] to do something.”(8) For many women, Nancy was an important female figure and may have been the first woman for many young readers who dared to defy the laws of society and adventure into the unknown.

Although Nancy Drew played an important role in Betty’s life, she was not the only reason for Betty’s growing independence. Betty’s father passed away her freshman year of high school, which left her mother without financial support. Other than renting rooms, Margaret had little opportunity to earn money for the family. As a result of this experience, Betty vowed to be independent both financially and emotionally in her adult life. Betty stated:

“I saw the impact on my mother, her concern about how the family would keep body and soul together, her lack of experience in business affairs. I decided I wanted to be able to take care of myself. I wanted to feel I could manage, I could cope. I didn’t want that kind of surprise.”(9)

This development inspired Betty to work at Kroger during her schooling years, not only to earn money, but because she enjoyed working.10 Although many women began working at this time, it was not usually out of interest but rather necessity. In the 1960s, “nine out of ten girls would work outside the home at some point in their lives, but each of the girls thought that she would be that tenth girl.”11 Rather than fall prey to the naive, helpless stereotype of women in the 20th century, Betty developed a strong sense of identity based on determination and individuality.

Upon graduation from high school, Betty attended Radford University, an all-female college located in Virginia. Although Betty was not ecstatic about this decision at first, she was sensitive to financial issues and maturely concluded that Radford was the most cost-effective solution. The University had a population of around only 1,000 students, allowing Betty to explore her “melange of interests” and accomplish just about anything she set her heart on doing.12 She became involved on campus, holding positions including junior class president, editor of the yearbook, and officer member of her sorority. Betty frequently participated in school dances with the male universities located nearby, an activity for which she needed parental permission to participate. When asked if she had any regrets about attending an all-female college, Betty said, “I just don’t think I would have been this assertive about making opportunities for myself.”13 Although the process of learning how to relate comfortably and easily with men was a limitation, Betty jumped over this hurdle upon enrolling in graduate school.

During her time at Ohio University in the Student Personnel Administration program, Betty had the opportunity to “catch up socially.”15 At Ohio University, Betty was a graduate assistant at Jefferson residence hall, a role that allowed her to evolve “from ugly duckling to something better.”16 Betty thrived in this role and quite enjoyed the dating process. In fact, Betty met her future husband, Dick Nelson, at Ohio University. Prior to meeting Dick, Betty had sworn she would never get married and thought she was unsuitable for a partner after a previous boyfriend had told her she was “too independent.”17 In fact, while reminiscing about her young adulthood and searching through old yearbooks, Betty found notes from her classmates stating she had chosen a “different path” than the rest of her female peers. However, rather than subscribe to the societal norms of the times or surrender to the comments of her classmates, Betty refused to marry only until she found a partner who respected her independence.

Just as Nancy Drew collected clues in the fictional town of River Heights, Betty Mitchell did her own sleuthing in Bluefield. Growing up without any strong female role models in her life, Betty had to discover for herself what it meant to be an independent woman in the 20th century. She learned to be an analytical thinker, broke out of the confining box in which most women lived, and didn’t need a “special friend” to find her way. Before Betty even stepped foot on Purdue’s campus, she was equipped with the tools to create the perfect storm of revolutionary change and female empowerment.

1- Klink, Angie. The Deans’ Bible: Five Purdue Women and Their Quest for Equality.

(Purdue University Press, 2014), 247.

2- Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski, 1 October 2019, Personal interview,

Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

3- Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski

4- Klink, The Deans’ Bible, 244.

5- Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski

6- Klink, The Deans’ Bible, 246.

7- Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski

8- Klink, The Deans’ Bible, 246.

9- Klink, The Deans’ Bible, 249.

10- Klink, The Deans’ Bible, 249.

11- Collins, Gail. When Everything Changed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2009, 17.

12- Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski

13- Klink, The Deans’ Bible, 251.

14- “1960 photograph of Peters Hall,” McConnell Library, Archives and Special Collections, Radford,Virginia. https://www.radford.edu/content/radfordcore/home/news/releases/2016/november/then-and-now-gallery2.html.

15- Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski

16- Klink, The Deans’ Bible, 253.

17- Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski

Primary

-Betty Nelson, interview by Anna Szolwinski, 1 October 2019, Personal interview, Purdue

University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

-Ellis, Joan M. “[Coal Tipple of the West Mine, Bluefield, W. Va.]” Photograph. N.d. From West

Virginia & Regional History Center, West Virginia History On View

-“1930 photograph of Peters Hall,” McConnell Library, Archives and Special Collections,

Radford, Virginia.

https://www.radford.edu/content/radfordcore/home/news/releases/2016/november/then-a

nd-now-gallery2.html.

Secondary

-Klink, Angie. The Deans’ Bible: Five Purdue Women and Their Quest for Equality. Purdue

University Press, 2014.

-Collins, Gail. When Everything Changed. Little, Brown and Company, 2009.