Posted on October 31, 2019 by small20

The “Black Salute” on Purdue’s Campus

by Max Malavenda

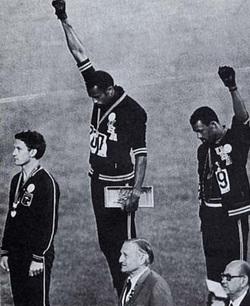

On the 17th of October during the 1968 summer Olympics in Mexico, two black American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, made history when, during the playing of the national anthem, the two men lowered their heads and raised their fists in what is known as the Black Power Salute.[1] Smith raised his right hand as a representation of black power,

and Carlos raised his left as a symbol of black unity, with both men wearing black gloves on their raised fists.[2] Smith and Carlos had, only moments before, become the gold and bronze medalists in the Mexico City held Olympic 200-meter race, respectively, with Smith having become the new world-record holder for the event, having completed it in 19.83 seconds. In addition to the salute, the two men also stood on the podium with no shoes but black socks, a symbol of black poverty, with Smith wearing a black scarf around his neck as a symbol of black pride, and Carlos wearing a bead necklace to honor black people who died by lynching in America as

well as unzipping his jacket as a show of solidarity with working class Americans, a background Carlos himself came from.[3] In what is now one of the most famous acts of civil protest of racial inequality in the world of sports, Smith and Carlos risked a lot with a seemingly simple gesture intended to raise awareness and inspire. In the immediate aftermath, not only were they two men removed from the Olympic games, they were bombarded with boos from the Olympic crowd, as well as condemnation back home from the media and the public in the form of death threats.[4] The two could not even find universal support within the rest of the United States Olympic team, with the late gold-medal boxer George Foreman stating in regards to their protest, “That’s for college kids. They live in another world.”[5]

However, as Foreman may have been surprised to learn at the time, such acts were not much easier or without consequence for college students either. One can conclude as much by taking a look at Purdue University’s history with a similar issue. Only nine days after Smith and Carlos’s Olympic protest, two black cheerleaders for Purdue University, Pam King and Pam Ford, began demonstrating the black salute during the national anthem at Purdue’s homecoming football game against Iowa.[7] The resulting controversy surrounding Pam King and the use of the black salute as well as the university’s, more specifically athletic director Guy “Red” Mackey’s response to the protest and other subsequent issues regarding race in Purdue athletics would not only be a blemish on Purdue’s history of its relationship to its minority population, but also serve as a microcosm of racial tensions in the country at large, reflected in events such as the Olympic protest.

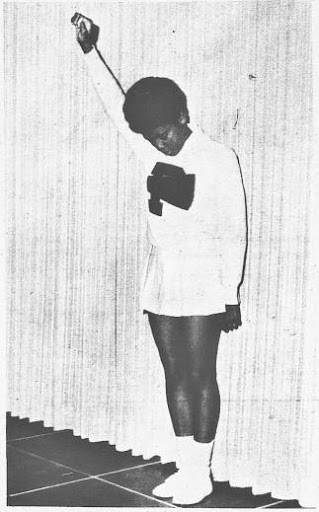

Upon King and Ford’s first use of the black salute, they were met with little resistance.[8] As King put it, once their fellow cheerleaders heard their explanation of the meaning of the salute, they, “agreed to allow us to continue if we would make others aware of the explanation.”[9] The explanation of the salute, as King would go on to give similar descriptions many times in the future, was that, “the Black Salute symbolizes the desire to make America a truly free country for all Americans (raised arm, clenched fist) and shame for the racial discrimination that American is now (bowed head).”[10] However, after subsequent uses of the salute by King and Ford, “Red” Mackey openly expressed his distaste for the salute to the captain of the cheerleading squad, and instructed the captain to tell the two not to carry on with it at future games.

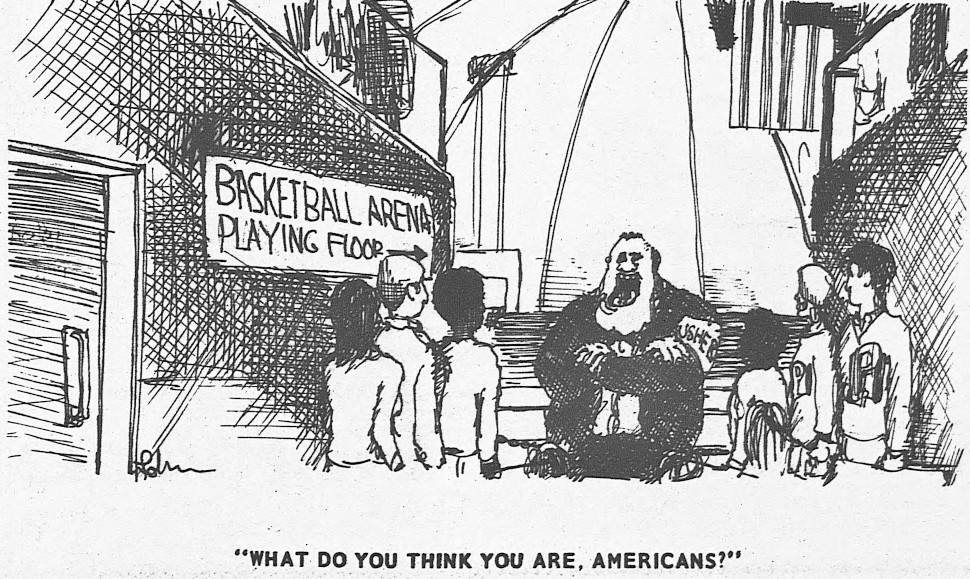

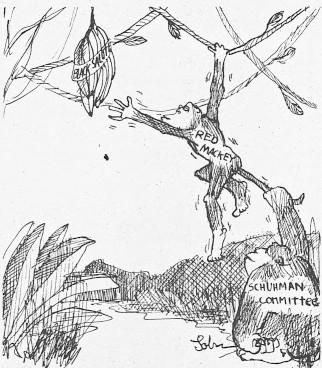

To any Purdue student, fan, or local, Mackey should be a familiar name. Guy “Red” Mackey was the athletics director of Purdue University for 29 years, the longest tenure of any Purdue athletic director in history, starting in 1942 and having retired from the position in 1971.[12] However, the average student more likely knows him as the namesake of Mackey Arena, home to Purdue men’s and women’s basketball. While Pam Ford ceased the black salute for fear of being removed from the cheerleading squad after Mackey made his disapproval known, Pam King went forward with the salute one more time at a home basketball game against North Dakota before both women decided to take the issue to Mackey himself.[13] As King recounted the interaction in an interview with The Exponent, “Mackey told us that he personally disliked the salute . . . but he said the decision was up to the cheerleading squad. He also said that if we were allowed to do the salute then he didn’t know what he would do.”[14] While not a reassuring response, the power to decide seemingly fell upon King, Ford, and their peers. A joint meeting between the cheerleading squad, the pep band, and the pep committee was held, in which it was upheld that King could maintain her position on the team, but that until they could reach a decision on the appropriateness of the black salute at sporting events, the cheerleading squad should remain off the court until after the playing of the national anthem.[15] However, this decision was not one supported by a majority of the cheerleading squad. Thus, in response the cheerleading squad for the following game voted four-to-two for the team to be on the court for the national anthem.[16] Yet, upon attempting to enter the court, the squad was denied access by direct order of Mackey. Upon attempting to reenter in civilian clothes, King was still denied access.[17] After performing as planned for the first half of the game, Pam King turned in her uniform and quit the cheer squad. What would follow were months of back and forth debate in hearing after hearing, leading to an eventual vote on the matter of whether or not King and other black athletes would be allowed to perform the salute.

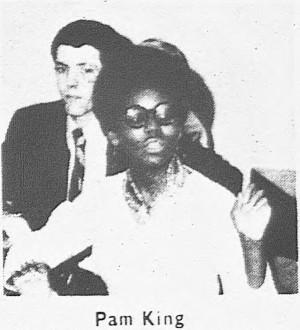

King was no stranger to protest and activism on her campus and community and would continue to be involved in such issues.She advocated for things such as the increased inclusion of blacks in the history of Purdue[19]. Simultaneous to the controversy surrounding her and the Black Salute she was also filing a formal complaint with the Lafayette Human Relations Committee against Gerald Clark, the principal of Sunnyside Junior High School,

on the grounds of racial discrimination after Clark cancelled a scheduled speaking engagement King had at the school on “Black Power and Black History” because the subject was, “too touchy.”[20] Even King’s position on the cheerleading squad was a point of controversy. In May 1968, the Black Student Action Committee, of which King was the activities chairman, had pressured the athletics department to accept two black cheerleaders to the squad for the upcoming academic year[21], those cheerleaders being King and Ford.[22] In the hearings following her barring from the

basketball game, King would cite this integration as a point of contention between her and her white squad mates, who thought by letting them on the squad, “they had done the blacks a favor . . . therefore they felt we owed them the favor not to do the salute,” King said.[23]

Beginning in January 1969, the hearings were to last until February 17th, on which date the committee would vote on a proposed resolution.[25] During this time, even Frederick Hovde, president of the university at the time, spoke out against the salute, claiming not to know its meaning (King had only weeks prior to this statement explained the meaning

personally to Hovde).[26] In the hearings led by a joint committee of the student senate leading up to the vote, while Mackey was invited to initial meetings, he was not invited to the later meetings. While he complained publicly about not being invited, saying he would be happy to attend, the student senate claimed they ceased to invite him because he indicated the exact opposite, that he would not be attending any hearings on the matter.[27] Luckily, Mackey’s involvement did not appear to be crucial, as on February 17th, a resolution was passed by a unanimous vote. The resolution stated, “The university should assume no official

position on the Black Salute. In particular, this expression does not furnish sufficient grounds for direct or indirect disciplinary action by university students, faculty, staff, or administrative voices.”

While the passing of the resolution was undeniably a success for King as well as the black student body at large, one would be hard pressed to trace any tangible change it caused. Mackey and the Purdue Athletics department would go on to have a continuously spotty record with black athletes for the remainder of 1969. In the weeks after the resolution vote, Pam King was supposedly the only former cheerleader not invited to a cheerleading

banquet, rumored to be at the request of Mackey. However, the event is still significant and unique when compared to other controversies surrounding Purdue’s black student body. First, this is one of the only major instances involving black students where a woman was both at the

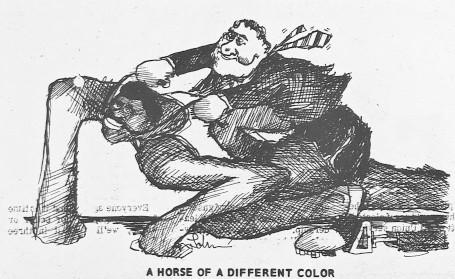

center of the issue and the forefront of combating it. Additionally, Pam King is unique in that among similar cases involving the Purdue athletics department, she is the only one at the time who would continue not only to be involved in the fight, but to be the main force by which the fight was fought. In comparison to her male counterparts at the time who clashed with Mackey and the athletic department, two black athletes prevented from running at the time due to their having mustaches and another who was prevented from receiving his varsity letter when by most accounts he qualified, all of whom were on the track team, none of them pushed the issue any further than the initial incident and subsequent reporting. If there was any pushback, it was not led by the students themselves, but by other relevant organizations such as the Black Student Union.

However, while this is an example of female excellence, it is not without its feminist critique. The most significant of which I would like to point out is King’s referring to the salute as the, “Black Man’s Salute.” While, when reading her thoughts on and meaning behind the salute and the issues facing black citizens, it may be clear that she is speaking of both black men and women, King is engaging in rhetoric that often leads to the exclusion of black women from movements of social change and political reform. Whether intentionally or not, this historic exclusion of black women from both the civil rights movement, with black men gaining the right to vote long before black women, as well as the feminist movement, with some of its origins tarnished by racism, is mirrored in King’s language when discussing the issue. In this way and in addition to the parallels between Pam King and Olympic athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith, we have another, less positive, reflection of Purdue culture contributing to the omission of black women from some of the most significant cultural movements of our country’s history.

[1] “1968: Black Athletes Make Silent Protest.” BBC News. BBC, October 17, 1968. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/17/newsid_3535000/3535348.stm.

[2] “1968: Black Athletes Make Silent Protest.”

[3] Boykoff, Jules. “Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and the 1968 Olympics: 50 Years Later.” Versobooks.com, October 16, 2018. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4088-tommie-smith- john-carlos-and-the-1968-olympics-50-years-later.

[4] Boykoff, Jules. “Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and the 1968 Olympics.”

[5] Ibid

[6] Tommie Smith and John Carlos making black salute at 1968 Olympics, “Poignant Moments In HISTORY.” eBaumsWorld, November 7, 2012. https://www.ebaumsworld.com/pictures/poignant-moments-in-history/82653187/.

[7] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” The Purdue Exponent, December 19, 1968, Vol. 84, No. 67, 3.

[8] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” 3.

[9] Ibid, 3.

[10] Ibid, 5.

[11] Pam King making black salute, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 142, 5.

[12] Purdue University Athletics. “Remembering Red,” Purdue University Athletics. Purdue University Athletics, December 2, 2017. https://purduesports.com/news/2017/12/2/Remembering_Red/.

[13] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” 3.

[14] Ibid, 3.

[15] Ibid, 5.

[16] Ibid, 5.

[17] “Who Wants An Anthem?” The Purdue Exponent, December 16, 1968, Vol. 84, No. 64, 5.

[18] Cartoon depicting the cheerleaders bar from entry during national anthem, 1968, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 64, 5.

[19] Paul J. Buser, “’Progressive’ Faculty?” The Purdue Exponent, May 16, 1968, Vol. 83, No. 137, 11.

[20] Kathie Barnes, “Formal Complaint Filed Against School Principal,” The Purdue Exponent, March 4, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 90, 1.

[21] Kent Hannon, “There Comes A Time,” The Purdue Exponent, May 23, 1968, Vol. 83, No. 142, 16.

[22] “Purdue Gets Two Negro Cheerleaders,” The Purdue Exponent, May 23, 1968, Vol. 83, No. 142, 16.

[23] Stephanie Salter, “Pam King Raises a Verbal Fist,” 5.

[24] Pam King attending attending Lafayette HRC hearing, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 90, 1.

[25] Meg Lundstrom, “Cheerleader’s Black Salute Becomes Issue Again,” The Purdue Exponent, February 7, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 73, 10.

[26] “We’d Like To Say Hooray,” The Purdue Exponent, December 19, 1968, Vol. 84, No. 67, 8.

[27] Bob Metzger, “Mackey Not Invited; More Talks Planned,” The Purdue Exponent, February 11, 1969, Vol. 84, No. 75, 1.

[28] Purdue Exponent cartoon depicting Red Mackey being stopped from touching the Black Salute by the Schuman Committee resolution, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 79, 8.

[29] Purdue Exponent cartoon depicting Red Mackey riding a black track athlete by their mustache, 1969, The Purdue Exponent Vol. 84 No. 113, 8.

Banner Image Reference in bold.